Companies have been cleared to seek seismic noise permits in the Atlantic, but ocean researchers fear for whales.

A North Atlantic right whale mother and calf swim in the Atlantic off the coast of Florida. Only about 500 of this species remain.

PHOTOGRAPH BY BRIAN SKERRY, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

PUBLISHED AUGUST 9, 2014

Whales talk. But what makes them stop talking?

Scientists have long known that the marine mammals use creaks, groans, growls, and buzzes to communicate with each other—often over long distances—to find food, and even for mothers to keep track of their calves.

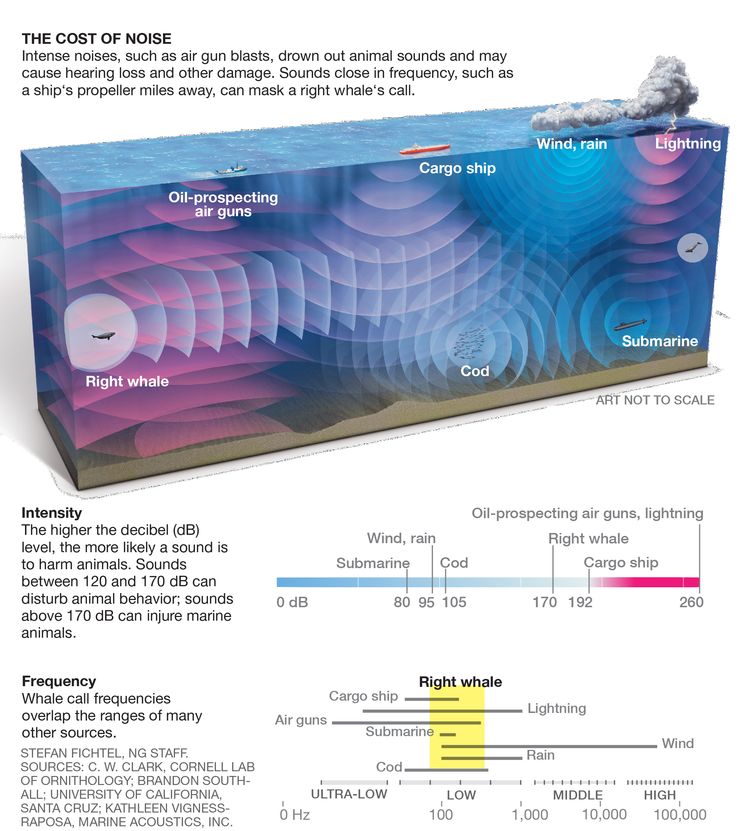

But what happens when the watery echosphere of their communication is filled with a drumbeat of undersea booms?

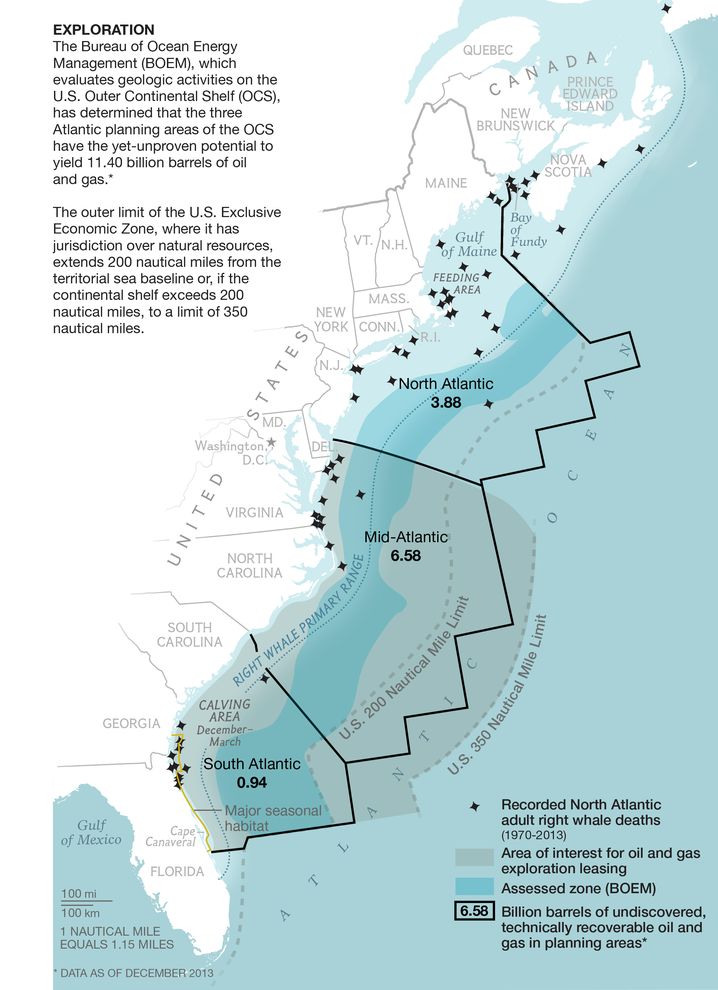

To the dismay of some who study whales, they may soon find out. The Obama administration this month gave the go-ahead for oil and gas companies to seek permits to use seismic noise cannons to map the Atlantic Ocean off the East Coast, to prepare for possible drilling after 2017.

Drilling companies already have carved up a target zone from Delaware to Cape Canaveral, Florida. The permits will allow their ships to crisscross the area dragging an array of cannons that erupt with a shock wave of sound every 10 to 15 seconds. The sound travels to the seafloor, enters the substrate, and bounces back to receivers on the ships.A diver gets up close to a right whale and her newborn calf off the coast of Argentina.

From the seismic pattern of those bounces, the companies’ geologists can make some good guesses about the location of gas and oil deposits under the ocean floor.

May Silence Whales

But some scientists believe the sonic booms will be a deafening cacophony to whales and dolphins, and may prompt them to stop communicating with one another.

“This is going to add more noise to the already huge problem whales are dealing with—man-made noise in the ocean,” said Sofie Van Parijs, who studies acoustics for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

“The long-term effects are not easily observed or clear,” she said. “They may not hear each other as well, find each other, find mates. Socializing, breeding, and foraging may be affected.”

The whales may just clam up. Douglas Nowacek, an associate professor of conservation technology at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, North Carolina, has studied whale behavior in the Gulf of Mexico, where seismic cannons are used extensively for seabed mapping.

In 2000, he and other researchers set off sonic cannons in a relatively quiet area of the Gulf and recorded the reactions of sperm whales. Those whales use what he calls “buzzes” to home in on fish at depths of 1,300 to 2,000 feet (400 to 600 meters), and especially to nab their favorite snack of giant squid.

When the scientists fired the cannons, “we saw the sperm whales tended to reduce the numbers of eco-buzzes. The rate of buzzes dropped off,” he said. If the cannons cut down on their feeding success, that’s not good for the whales, he noted.

Singing Patterns Changed

This behavior was similar to that of humpback whales in the Mediterranean. Faced with noise interference, the whales changed their singing patterns over long periods, Nowacek said.

The researchers are particularly concerned about the majestic North Atlantic right whale. The right whales’ documented response to sudden noises is to shoot for the surface, and then remain just under water.

“That’s a terrible place for right whales to be,” said Michael Jasny, director of the marine mammal protection program for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

When they hover just under the surface, the whales are vulnerable to becoming aquatic road kill for the ships that do not see the animals.

The species was nearly extinguished by whalers, who found that their thick blubber and propensity to float near the surface made them the “right whale” to hunt. The ban on commercial whaling in 1986 has helped other species rebound, but the North Atlantic right whale has struggled. Because it is often near the surface, its biggest threat now is ships.

Only about 500 of the whales remain, and scientists keep meticulous track of them. They scour the waters to monitor the whales, and keep careful photo records of each known whale, often identified by the scars from the animal’s encounters with propellers or bruises from hull strikes.

“It’s critical to understand that the ocean is an acoustic world,” Jasny said. “Many species—whales, dolphins, fish, invertebrates—depend on their hearing, and the ability to be heard, for survival and to reproduce.

“Air-gun surveys put out more noise than any other human source short of dynamite,” he said. “Human noise can destroy the ability of right whales to communicate. If the whales are silent, then that means they are unable to feed cooperatively, unable to find mates. A silent whale is, for all intents and purposes, blind.”

Another Viewpoint

But those predictions of grave effects on whales are rejected by theBureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

“I think those assertions are wildly exaggerated and not supported by the evidence,” William Y. Brown, BOEM’s chief environmental officer, said in an interview.

The agency issued the decision July 18 allowing drilling companies to take the first steps toward exploration of the East Coast waters, a move promised by President Barack Obama in 2010 but delayed by theDeepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“The real question is whether [whales] are just hearing a noise and turning around, or whether it disrupts them in a way that makes them move away from food or disrupts breeding,” Brown said. “There’s just no evidence that happens.”

The bureau, part of the Department of the Interior, insists it has taken every precaution. To help “mitigate” the seismic blasts, BOEM ordered that mappers must watch and listen for whales, motor slowly and stop if a whale comes near, avoid right whale breeding grounds in the spring, and take other measures.

Critics said those steps are too meager. The American Petroleum Institute, on the other hand, complains they are unneeded. “Operators already take great care to protect wildlife, and the best science and decades of experience prove that there is no danger to marine mammal populations,” the oil industry association said in a statement.

A federal environmental impact statement released in February asserted most impacts to sea life would be “negligible or minor, and no major impacts were identified.”

The Atlantic area involved contains some thousands of species, including 39 mammal species, seven of them endangered: the humpback, sperm, fin, blue, sei, and right whales and the West Indian manatee, according to the environmental impact statement.

“We should be concerned about effects of sound on marine mammals and make sure it doesn’t hurt them,” Brown said. “But I am pretty sure the overall noise level in the Atlantic will only be incrementally affected by these surveys. There are orders of magnitude more noise from vessel traffic.”

Whales vs. Ships

Scientists already have seen a dramatic, if tragic, demonstration that shipping traffic is weighing on the whales.

Susan Parks, an assistant professor of biology at Syracuse University in New York who studies whale acoustics, and Rosalind Rolland of the New England Aquarium in Boston, who studies stress hormones in right whales, were working on September 11, 2001, the day of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C.

When the world’s ships docked for a week following the attacks, the seas went quiet and the stress-level indicators “showed a dramatic drop that we haven’t seen any other years,” she said.

The finding showed that the whales are much more affected by human behavior than we might have thought, Parks said.

“We just really don’t know what it’s going to do, but we know these are endangered species that are going to be put in harm’s way,” she said.

Doug Struck is a veteran journalist and teaches at Emerson College in Boston.