Eric Carpenter shrugs. The director of Miami Beach’s Public Works Department sits at his desk, poring over tables of high tides on his computer. He is calculating how many pumps he needs to buy to keep the city’s streets from being flooded from a rising sea caused by climate change.

Under a broiling sun, he takes a visitor a few blocks from his office, to where contractors are pouring concrete to replace a section of a city street. The new roadway is being laid incongruously 2-1/2 feet above the sidewalk cafe tables and storefront entrances at the old street level. The extra height is in preparation for the seas and tides that Mr. Carpenter already sees engulfing this section of Miami Beach.

“The facts are the facts, and we have to deal with them,” he says.

This groundswell of action on climate change is producing solutions and often bypassing lagging political leadership. The gathering force of these acts, significant and subtle, is transforming what once seemed a hopeless situation into one in which success can at least be imagined. The initiatives are not enough to halt the world’s plunge toward more global warming – yet. But they do point toward a turning point in greenhouse gas emissions, and ambitious – if still uneven – efforts to adapt to the changes already in motion.

“The troops on the ground, the local officials and stakeholders, are acting, even in the face of a total lack of support on the top level,” says Michael Mann, a prominent climate scientist at Pennsylvania State University in State College, Pa. “The impacts of climate change are pretty bad and projected to get much worse if we continue business as usual. But there still is time to avert what we might reasonably describe as a true catastrophe. There are some signs we are starting to turn the corner.”

Philip Levine, the mayor of Miami Beach, agrees. “We may not have all the answers,” he says. “But we’re going to show that Miami Beach is not going to sit back and go underwater.”

The record of past such meetings is not encouraging. But the representatives will arrive as progress on curbing greenhouse gas emissions, often overlooked, has been mounting:

•Wind and solar power generation are bounding ahead faster than the most optimistic predictions, with a fivefold increase worldwide since 2004. More than 1 in 5 buildings in countries such as Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and even Albania are now powered by renewable energy.

•The US saw its greenhouse gas emissions peak in 2007. They have fallen about 10 percent since, and are roughly on course to meet President Obama’s pledge to reduce emissions in the next 10 years by about 27 percent from their peak.

•China, the world’s largest carbon emitter, paradoxically leads the world in installed wind and solar power, and is charging ahead on renewables. China and the US ended their impasse over who is most responsible to fix global warming, agreeing in November to mutually ambitious goals. Experts say China already has cut coal consumption by 8 percent this year, and the environmental group Greenpeace says China stopped construction of some new coal power plants.

•Worldwide, carbon dioxide emissions, a principal component of greenhouse gases, did not grow in 2014, according to the International Energy Agency. Emissions remained flat even as the global economy grew – an important milestone.

•Coal-fired power plants are being replaced rapidly by natural gas plants, which are cleaner and emit half the greenhouse gases. Britain saw an 8 percent drop in greenhouse gas emissions last year, which is attributed to national energy policies, more energy efficiency, and the switch from coal.

•Tropical rainforests, which absorb carbon dioxide, are being cut down at a slower rate than in the past – 13 million hectares per year, compared with 16 million in the 1990s, according to the latest figures from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. That is still alarmingly high but shows progress, in part because of vows by big corporations not to buy palm oil grown on deforested lands. Brazil has made notable progress in reducing deforestation of the Amazon.

In the US, state and local governments are taking bold action even as the national discussion about the looming climate crisis remains paralyzed along political lines. In South Florida, for example, officials of four populous counties shun the rhetoric from GOP presidential aspirants and officials in the state capital and gather regularly to plot cooperative climate change strategy.

That group, the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, is considered a national model for the kind of shoulder-to-shoulder effort needed to address the problem. They came up with an agreed estimate of sea level rise and identified the most vulnerable areas of the region, and now are plowing through more than 100 recommendations for action.

“There are no new funding sources coming down from the state or the Feds,” says Susanne Torriente, assistant city manager for Fort Lauderdale, one of the participants of the compact. “Would it be good to have state and federal dollars? Yes. Are we going to wait until they act? No.”

Their cooperation was born, essentially, on the back of a napkin. Kristin Jacobs, now a state representative who was a Broward County commissioner in 2008, was lamenting at the time that the 27 disparate municipal water authorities in the region could not agree on joint action. So she and others came up with the idea of getting local officials together in a classroom.

“We said, ‘Let’s have an academy,’ ” she recalls, and the Broward Leaders Water Academy began offering elected officials in South Florida six-month courses in water hydraulics and policy. It has now graduated “three generations of elected officials,” she says.

Figuring out what to do about climate change – whether it is building up dunes on the beaches, raising the height of foundations, or shifting developments back from the coastline – takes a cooperative approach. “We couldn’t do it by just saying ‘this is the way it is’ – the Moses approach,” Ms. Jacobs says. “We had to do it with compliance and acquiescence and leadership.”

Normally, direction on some of these issues might have come from state officials. But not in Florida. Not on climate change.

“We didn’t have to worry about those who don’t believe,” Jacobs says. “At the end of the day, when the water is overtopping your sea wall, you don’t really care that you didn’t believe in climate change last week. You do believe in it this week.”

• • •

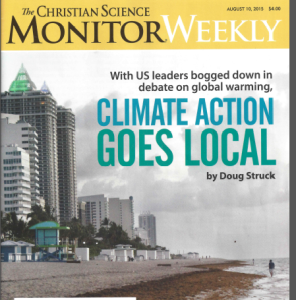

Built on the edge of the sea, Miami Beach is one of the most vulnerable cities in the world to the vicissitudes of the ocean. Its boutique commercial district and canyons of pastel apartments sit on a sieve of porous limestone. The leaky footing was formed over the eons from accumulated seashells, coral, and fish skeletons.

Today the rock acts as a giant wick, giving the relentless ocean a route for subterranean attack. Seawater pushes in from underground and often gurgles to the surface in inconvenient places. On days of really high tides – even without any rain – the briny invasion turns some city streets into small lakes, snarling traffic and cutting off businesses. Locals call it “sunny day flooding.”

The man charged with stopping the sea – or at least getting tourists and residents out of its way – is Carpenter, an affable engineer with a burly physique. Carpenter took over the city’s Public Works Department two years ago. His recurring nightmare is of rising seas, frequent storms, and “king” tides sweeping through Miami Beach – and doing it in full view of the world. He knows that whatever the city does – or does not do – to prepare for climate change will be tested soon on a stage before a global audience.

“What we do here is magnified because of who we are,” he says. Miami Beach thrives on a global reputation for glamour, for cultural fusion, for beaches, for heat – from the sun in the day and its epicurean club culture at night. That’s not an image that sits well with flooded streets. But the water is already coming.

As the Atlantic Ocean warms and expands, fed by melting polar ice caps, the seawater is pushing back into the 330 storm-water pipe outlets designed to drain rain from city streets. So Miami Beach is in the process of installing as many as 80 pumps, at a cost of nearly $400 million, to make sure the water flows outward.

“If the seas are continuing to rise, and the tidal events are higher than the inland elevation, we have to pump,” says Carpenter.

The city plans to raise the level of 30 percent of its streets, encouraging businesses to abandon or remodel their first floors to go to a higher level. Carpenter says he wanted to go up nearly six feet, but town officials said “we are going too fast.” So they settled on just over three feet.

“I don’t think this is where we want to be long-term, but it’s enough to get us through the next 10 or 20 years,” he says, while standing on a new section of road at Sunset Harbor, looking down at the cafe tables on the sidewalk below, where the street used to be.

Mayor Levine echoes the importance of dealing with the future encroachment of the sea – now. “We did not ask for climate change or sea level rise,” he says. “But we are the tip of the spear. We don’t debate the reason why; we just come up with solutions.”

Forty miles to the north, past Fort Lauderdale, Randy Brown and his utilities staff in Pompano Beach are also trying to halt the sea. Like the rest of South Florida, the coastal city of 100,000 residents is confronting the ocean above and below ground.

They are burying a new network of water pipes – painted grape purple – running to businesses and homes. The pipes contain sewer water that has been treated to remove the smell and bacteria and then siphoned from a pipe that used to discharge it into the sea.

Pompano Beach residents use the water for their lawns and gardens, bypassing the restrictive bans on lawn sprinkling. This recycled water then trickles down into the Biscayne Aquifer.

Cleansed as it sifts through the ground, it helps reduce the shrinking of the freshwater aquifer, which is being drawn down by the town’s 26 wells and is threatened by underground salt water pushed inland by the rising sea level. Homeowners pay about two-thirds less for the recycled water than they do for potable water.

When city officials first laid out the program at a public meeting, bringing a cake to set a neighborly tone, “it was a fiasco. [Residents] called it dangerous,” chuckles Maria Loucraft, a utilities manager.

Now, people “say they can’t wait for it to get to their area,” adds Isabella Slagle, who goes to public events with a mascot, a purple-colored sprinkler head with sunglasses, named “Squirt” by elementary school students.

Green lawns trump the political arguments over climate change, says Mr. Brown. “We don’t say ‘climate change,’ ” he admits. “It’s ‘protecting resources’ or ‘sustainability.’ That way, you can duck under the political radar.”

Some don’t want to avoid the radar. Last October, the South Miami City Commission voted to create “South Florida” and secede from the rest of the state, in part because, they said, the state government in Tallahassee was not responding to their pleas to help them deal with climate change.

“It got a lot of press but nobody in the state took it very seriously,” muses the mayor, Philip Stoddard, over a sandwich on the campus of Florida International University, where he is a biology professor. “But it did get people talking about climate change.”

“My house is at 10 feet elevation,” he adds. “My wife and I – our question is – will we be able to live out our lives in our house? I’m 58. We don’t know. It’s going to be a close one. If you look at the official sea level projections, they keep going up, which is a little disquieting. If you look at the unofficial projections, they scare the hell out of you.”

While South Florida is a leader at local cooperation, officials in towns and cities across the country are struggling to react to a warming climate. Many municipalities have drafted action plans. Boston is converting its taxis to hybrids and requires new buildings to be built with higher foundations. Chicago is planting green gardens on city roofs to reduce the air conditioning needed to cool buildings. Seattle is helping residents install solar panels. Montpelier, Vt., vows to eliminate all fossil fuel use by 2030. Houston is laying down “cool pavements” made of reflective and porous material, and planting trees for shade.

Governors and state legislators across the country have gotten the message, too. While Congress will not debate the “Big Fix” – putting a price or a cap on carbon pollution – some states are already doing it. About 30 percent of Americans live in states that have rules capping carbon dioxide emissions and markets that allow companies to buy and sell carbon credits.

In addition, 28 states have set mandatory quotas for renewable energy from their electric utilities. Seven states have set ambitious targets for overall greenhouse gas reductions – California has promised a reduction of 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

“The best thing Congress can do right now is stay out of the way,” says Anna Aurilio, director of the Washington office of the nonprofit advocacy group Environment America. Between the state efforts and the executive orders by Mr. Obama, she says, the US is on track to meet the administration’s greenhouse gas goals.

“When we look at programs currently in place or set to be implemented, we can come close to the US commitment” of a 27 percent decrease in greenhouse gas emissions in 10 years, she says. “But we know we have to go much, much further.”

To get near the goal of keeping average global warming at 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) or less, climatologists predict that countries must largely abandon the fossil fuels that have driven technological societies since the Industrial Age – achieving an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

That is an imposing goal, since billions of dollars are invested in new and existing fossil fuel power plants that can last 30 to 50 years. Even if solar or wind energy is cheaper than coal, oil, and natural gas, the owners of fossil fuel plants will be reluctant to abandon their investments. But the decisions are starting to come from the people, not just governments or corporations.

“When you have enough action taking place at the grass roots, sometimes that’s a more effective means of implementing change on a large scale,” says Penn State’s Mr. Mann.

• • •

Nicole Hammer is one of the foot soldiers in the new war on global warming. A biologist, consultant, and former assistant director of a university center on climate change, she quit and decided to work with nonprofit groups, including the Moms Clean Air Force, an organization that campaigns to stem air pollution and climate change.

“I realized we have more than enough science to take action on climate change,” she says while walking at an ecology park near her home in Vero Beach, Fla. “People who normally wouldn’t be involved in environmental issues are starting to speak out.”

She believes community involvement is the key to solutions, because the problems are felt most keenly at that level. “We have people in communities who have to put their kids in shopping carts to get across flooded streets to get food,” she says. “When you see that happening – and then you see people at high levels denying it – it’s disappointing and it’s incredibly frustrating.”

Public outcry has helped close coal-burning power plants, which produce the dirtiest energy. Coal plants now provide about one-third of the electricity in the US – down from more than half in 1990. Tightening pollution standards and cheaper natural gas prices have prompted utilities to close 200 coal-fired plants since 2010, the Sierra Club estimates, and the trend would only accelerate under new clean air regulations unveiled by Obama in early August.

Until recently, one argument against closing coal plants was that if the US didn’t burn its own abundant coal reserves, they would just be exported to China. But Chinese authorities are so sobered by their public’s resentment of the thick coal soot and industrial pollution that they are turning with startling speed to renewables. China reached a significant agreement with the US in November to cap its greenhouse gas pollutions by 2030, and further impressed experts in July by promising to ramp up renewables to provide 20 percent of its power, a sharp turn away from its pace of bringing a new coal power plant on line every 10 days.

“China has become a policy innovator,” says Nathaniel Keohane, vice president of the Environmental Defense Fund, who worked on international climate issues in the Obama administration.

Other countries are plotting their own ways to curb greenhouse gases. Germany, Italy, Japan, and Spain are ramping up solar energy. France has embraced nuclear. Denmark, Portugal, and Nicaragua led in wind power in 2014. Brazil is adding hydroelectric plants as well as sharply reducing deforestation. Kenya and Turkey are tapping geothermal power. And smaller countries such as Costa Rica, Iceland, and Paraguay have found financial and tourism benefits in being at or very near “carbon neutral.”

Still, the current projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on when the world will see a significant decline in global emissions vary widely – from about 2030 to after 2100 – based on guesses of how countries respond. But the dramatic shift to natural gas in the US, and the racehorse expansion of hydraulic fracturing to get it, are demonstrations that if new technologies are profitable, industries can pivot quickly.

“We can make that turn,” Mr. Keohane predicts. “Imagine the day when emissions are falling instead of rising. Imagine when we are winning rather than losing.”