NECIR link to story

Raw Sewage Continues to Contaminate Waterways in New England

By Doug Struck

New England Center for Investigative Reporting

Arpil 21, 2013

Billions of gallons of raw sewage and contaminated stormwater surge every year into the waterways and onto the streets of New England, as a 40-year-old pledge to clean America’s lakes, rivers and streams remains unfulfilled.

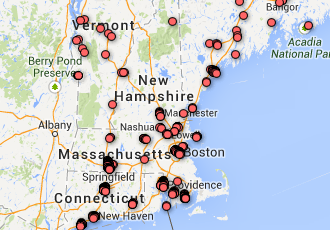

That is the conclusion of a six-month inquiry by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting—the first comprehensive look at where, how often and how much sewage flows into New England waterways, and the first to map the peril. (see accompanying maps)

“I’m certain the general population is unaware that raw sewage is being discharged to their streets and rivers,” said the executive director of the Mystic River Watershed Association, Ekongkar Singh Khalsa. “I’ve walked around Wellesley or Newton after a storm, and suggested people should not let their dog walk on this. They thought I was mad.”

Stormwater, burst pipes and antiquated infrastructure turn manholes into geysers and basements into fedtid pools of sludge—all due to accidental overflows. But the largest assault on our waterways is a design fault hidden underground: old sewage systems that mix storm runoff with raw sewage and propel the contaminated combination, untreated, into rivers, streams, harbors and bays.

Massachusetts, the most populous New England state, produces the most of these “combined sewer overflows,” despite decades of investment in sewage systems in Boston and other municipalities. In 2011, approximately 2.8 billion gallons of sewage water spilled through 181 pipes throughout the state. The NECIR investigation determined more than 7 billion gallons spewed into waterways across New England, the first such compilation of an annual total. (see chart)

Connecticut discharged about 1.5 billion gallons through 125 active “outfall” pipes, while Maine and Rhode Island put more than 1 billion gallons into their waterways. (See accompanying chart.) These discharges send contamination levels soaring after rainfalls, closing beaches and prompting bans on shellfishing.

“I don’t swim in waters right after it rained,” said Suzanne Condon, director of the Bureau of Environmental Health at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. “I am pretty confident that there’s going to be a problem.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has identified 772 communities across the country that routinely discharge sewage into water.

The NECIR investigation found 65 of those towns and municipalities in New England had sewage overflows through 450 pipes overwhelmed by wet weather in 2011, the latest year for which data was obtainable from most states.

The Clean Water Act, passed at the peak of environmental optimism in 1972, dictated that the nation stop polluting its waters by 1985. Environmental experts say striking progress has been made, though much still needs to be done.

In New England, Boston Harbor and the Charles River are national symbols of how rescued waterways can become jewels of development and civic pride. Hartford embraced the cleaned-up Connecticut River with a popular park system on the once-shabby waterfront. Rhode Island is rejuvenating the sewage-crippled Narragansett Bay. Fish are returning to Maine’s Androscoggin River, once so foul and foamy the oxygen level reached zero.

But a review of the sewage system records for the region’s six states by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting shows how short we have fallen from the ultimate goal to fully stop polluting New England’s waterways. In 2011, sewage system operators in New England reported more than 7,700 instances when raw sewage, mixed with dirty stormwater, bypassed treatment facilities and was dumped into rivers, bays and the ocean.

Although the New England states have spent billions on new sewage systems, often under court order, each state still has regular– sometimes massive- discharges of contaminated water.

“The more intense the storm, the worse the quality of the stormwater pipes,” said Roger Frymire, 56, a retired Cambridge software designer who has spent 17 years kayaking, canoeing and wading the Charles River and other waterways to get water quality samples.

“I started because every time I would launch my canoe, no matter if I went upstream or downstream, I’d smell sewage. I got sick of it,” he recalled. “Pure raw sewage going into the river is pretty bad. I’ve seen everything from a subsurface pipe with brown turds bobbing to the surface in front of it, to dense gray water around Storrow Drive in Boston.”

All states are required to regularly monitor bacterial levels in their waterways. But the EPA says it does not compile public records of where and how much sewage flows into those waters. Each state is supposed to report that information, but the NECIR inquiry found the data is often incomplete, inaccessible, sometimes handwritten and sometimes based on little more than guesswork, undermining the public accountability built into the Clean Water Act.

In Rhode Island, for example, none of the 54 discharge pipes of the Narragansett Bay Commission is monitored, though the state insists it can estimate the sewage output total: 1.18 billion gallons in 2011. “Individual volumes and discharges for each pipe are not available,” said Tom Brueckner, engineering manager at the commission.

Because the sewage is diluted and disperses, regional health authorities say it is difficult to definitively link any particular instances of disease or infection to these discharges. But sewage carries pathogens—bacteria, parasites and viruses—as well as chemical toxins. The pathogens can cause infections, dysentery, and potentially even cholera. For high risk populations—children, the elderly and those with immunity—the result could be serious, even deadly.

An often-cited EPA estimate from 2004 concluded between 1.8 and 3.5 million Americans get sick annually from recreational contact with sewage-contaminated waters.

Health authorities in Massachusetts closed public swimming beaches 915 times in 2011 because of high bacteria from stormwater runoffs and sewage overflows, an act echoed by other coastal states.

In addition to beaches, coastal states regularly ban shellfishing because of pollution. Rhode Island, fearing sewage-born bacteria, routinely closes 11,000 acres of shellfishing when it receives a half-inch of rain or more. Maine’s Department of Natural Resources lists 105 shellfishing areas closed this winter.

The problem persists because the goals of the Clean Water Act turned out to be far more costly than expected. The law was born in the blush of environmentalism that produced the first Earth Day, the Clean Air Act, and the Environmental Protection Agency, all in 1970, and laws on coastal zone management, marine mammal protection, insecticides and the Clean Water Act in 1972.

When the Clean Water Act was passed, two-thirds of the country’s lakes and rivers were unfit for swimming, according to 2002 congressional testimony. Today, that has been halved. The EPA estimates the federal government spent $61 billion on sewage treatment systems from 1972 to 1995.

The benefits are visible. The Charles River “really ran in colors” in the mid-1960s because animal body parts were dumped in the water from slaughterhouses, said Bob Zimmerman, executive director of the Charles River Watershed Association. Now, after an expenditure of $79 million, the Charles is now called the country’s “cleanest urban river,” Zimmerman said.

Boston Harbor was a cesspool four decades ago. After an expenditure of $5.5 billion dollars, construction of a new treatment plant on Deer Island in 1995 and a massive underground tunnel in 2011, the Harbor is much cleaner. Nitrogen overloads have plunged by 50 percent, oxygen has increased, and the sea grasses that once coated the harbor floor are returning, according to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority.

“There’s no question the Clean Water Act has improved water quality in the places we measure water quality,” said Denny Dart, chief of Water Enforcement for EPA’s Region 1, covering New England. “It certainly has prompted immense investment in municipal infrastructure. We’ve built sewage treatment plants, laid new sewer lines, done an immense amount of work to handle human waste. There is still much to do. In New England, where the pipes are a century old, it’s time to replace much of it.”

“There have been millions and millions of dollars spent on this,” said Ann Lowery, deputy assistant commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. The state helps municipalities fund projects and since 1999 has spent about $1 billion of the roughly $4 billion needed, she said. “The frequency [of discharges] has been reduced, and the volume has been reduced, and they continue to be reduced,” she noted.

But increased population brings more development that paves over green areas and increases storm runoff. And climate change is expected to bring higher water levels, more frequent storms and more severe rainfall to New England.

The pollution comes in two ways. What officials call “sanitary sewer overflows” are direct discharges from the sewer lines themselves, often caused when pipes are ruptured, clogged with grease or tree roots, or flooded in a rain. This can cause backups that send raw sewage spilling onto streets or spouting from manholes.

In 2004, the EPA estimated 3 to 10 billion gallons of untreated sewage is leaked accidentally each year in this manner.

“Most people don’t know much about what goes on underground,” said the EPA’s Dart. “When we get big storms and flooding I see people letting their children play in the floodwater. In New England, there’s a very good chance that the floodwaters have sewage in them.”

But the biggest source of pollution – an estimated 850 billion gallons each year– comes as a result of a design shortcut, according to a 2004 report to Congress by the EPA. Many East Coast sewage systems were designed to funnel stormwater runoff, which picks up contaminants, into the same treatment plant that handles sewage. In routine weather, this generally works, and has the advantage of cleansing both stormwater and sewage before it reaches waterways.

But when there are heavy rains or snowmelt, the systems are overwhelmed, and operators divert the deluge directly into the waterways. These events are called “combined sewer overflows.”

To fix the problem, municipalities can build separate systems for sewage and stormwater, or build immense underground holding tanks to hold the excess until it can be treated. Vermont has invested $600 million in wastewater treatment facilities since the 1970′s; its rivers no longer turn the color of the dye used in woolen mills. Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay Commission tunneled under Providence to construct a three-mile long, 26-foot wide holding tank for stormwater. Connecticut halved its sewage outfall pipes in 30 years. New Hampshire has enlisted volunteers to monitor 180 lakes and is protecting its shoreline.

But the size of the work yet to be done is daunting. The EPA still lists nearly 3,000 water bodies in New England as “impaired,” meaning they remain too polluted to meet the minimum water quality standards set by the states.

The federal government paid the bulk of sewage treatment improvements at the beginning of the Clean Water Act, but by 1987 it reduced its contribution to a fund that makes about $5 billion in low-interest but repayable loans to the states each year to finance water quality projects. The burden is largely on hard-pressed local and state governments to pay for continued progress; in 2008 the EPA estimated that another $64 billion is needed to fix the combined sewer problems, $4.2 billion of that in New England.

“It’s probably the biggest issue in town,” Nicole Clegg, communications director for Portland, Maine, said of the cost of sewerage improvements. “We have invested $100 million already and will invest $270 million over the next 15 years. Everybody is invested in having a clean Casco Bay. Portland’s quality of life attracts businesses. That said, there are real concerns that our [utility bill] rates are becoming so high we are losing our attractiveness to businesses.”

“The most important thing for people to become more aware of is we are still using rivers and streams as sewage conveyances,” said Khalsa, of the Mystic River Watershed Association. “What’s needed now,” Khalsa said, “ is to look at the great work we’ve done, and redouble our efforts to complete the job.”

The New England Center for Investigative Reporting (www.necir-bu.org) is a nonprofit investigative reporting newsroom based at Boston University. Emerson College journalism student Vjeran Pavic helped compile the mapping for this project.

Chart

Combined Sewer Overflows in New England, 2011

(Sources: State and local environmental agencies.)

| State |

Number of Towns with Sewage Discharge |

Total Number of Active Discharge Pipes in 2011 |

Total Number of Active Discharges in 2011 |

Volume of Sewage Water Discharged in Millions of Gallons |

| Maine |

26 |

57 |

1281 |

1141 |

| Conncticut |

4 |

125 |

2505 |

1469 |

| Vermont |

7 |

7 |

14 |

unk |

| Rhode Island |

5 |

58 |

unk |

1180 |

| New Hampshire |

6 |

22 |

401 |

513 |

| Massachusetts |

17 |

181 |

3547 |

2774 |

| Totals |

65 |

450 |

7748 |

7077 |

Maps

New England Region

Massachusetts

Maine

Rhode Island

New Hampshire

Vermont

Conneticut

SHARE THIS!