To read story in The Washington Post , please go here.

In a city of freeways and showbiz, live-broadcast cop chases are ‘great spectacle’

By Doug Struck. December 15, 2021

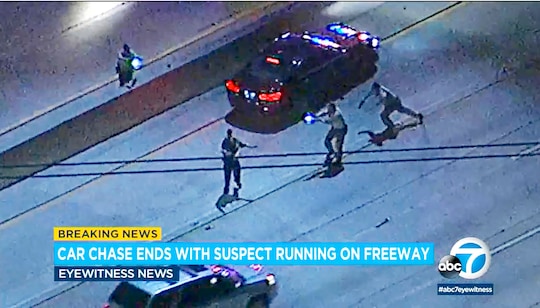

LOS ANGELES — As reality TV shows go, this was a good one: A guy carjacked a Honda, sped against traffic on Interstate 5, twice was cornered by police, once got out of his car to be bitten by a police dog, then angrily took off again.

KTTV’s helicopter team covered it for three hours, providing breathless aerial play-by-play to fascinated viewers. But just as the cops reached a standoff with the suspect, the station cut away to more breaking news. A hijacked utility truck was careening down another thoroughfare, police in full pursuit.

Los Angeles, the city of freeways, wallows in the drama of live-broadcast police chases. These occur with stunning regularity, and if Variety weighed in, the reviews would be boffo: “Mesmerizing!” “Breathtaking action!” “Couldn’t stop watching!”

Dozens of times a year, some desperado pushing the limits takes off in a stolen or getaway vehicle, trailed by a line of flashing lights and sirens and, overhead, a squadron of television station helicopters.

The airborne videographers zoom in tight at each intersection, as viewers hold their breath at the chance of a violent crash with some innocent commuter. The copter cameras swoop in as vehicles finally roll to a stop, often out of gas or limping on tires flattened by spikes thrown down by police. Viewers follow along if the driver bails from the car and sprints through a residential neighborhood. The pilots generally hover long enough to show suspects getting handcuffed.

At which point the stations switch back to their regularly scheduled programs.

Other cities have police chases. But Los Angeles has all the trappings to make it a grand event — endless eight-lane highways, a flat cityscape, a culture of cars.

“The freeway basically touches almost everyone’s lives. It’s central to the [city’s] identity,” said University of California at Los Angeles professor Tim Groeling, who studies political communication. But that’s not the only explanation.

“This is where Hollywood is. And the pursuits are a great spectacle,” Groeling noted. “I know the telltale sound of multiple helicopters in formation on the freeway, and I’ll turn the TV on to see who’s doing it this time.”

Often leading the formation is KTTV’s Stu Mundel — a “famed” helicopter reporter, according to Variety, largely because of his coverage of chases. He is a student of the genre, calmly detailing police strategy as he shadows a scene.

“They are not going to do anything quickly. Everything will be planned,” he explained during the recent chase of that Honda’s alleged carjacker.

Mundel, who sports a gray beard and wears rock band T-shirts, thinks the audience appeal is basic: “You’ve got a good guy. You’ve got a bad guy. You’ve got the Greek story of the struggle between good and evil.”

One of his competitors, Mark Kono of KTLA, brings a sports fan’s fervor. “Take this guy into custody,” he urges the home team in blue. “Oh, jeez,” he moans when officers fail to make the stop. “C’mon, it’s time to go to jail, time to give up,” he hoots at suspects.

These moment-by-moment broadcasts have shown police tracking hot cars and Hondas, Teslas on autopilot with sleeping drivers, tractor-trailers and utility trucks. In one chase, the driver of a gigantic recreational vehicle sheared off its side and windshield before she jumped out to flee with two dogs.

There have been suspects who took off on horseback into the desert and go-cart drivers on the freeways. Motorcyclists have the best chance of getting away if they are clever; one guy stopped under an underpass, safe from the cameras above, and slipped away in a culvert. Another ditched his cycle at a mall and changed his clothes inside. When he tried to sneak out, the copter crews spotted his bright green sneakers.

Deadpans Mundel: “We don’t assume these suspects are smart.”

Through November, Los Angeles police had engaged in 910 pursuits this year. Most were quick, though nearly a quarter ended in injuries or death. According to Al Pasos, who heads the traffic division, officers do not chase cars for traffic violations or speeding, and commanders oversee all pursuits, with the authority to call them off depending on the circumstances.

Chief Michael Moore has grumped at the coverage, calling it “too glamorized at times . . . too sensational.” These situations are “not a video game,” he stressed.

Yet the in-air reporters defend their work, saying their reports can help clear neighborhood streets and minimize the danger to others.

“It’s journalism,” said KABC’s Chris Cristi. “At the end of the day, it’s informing and telling a story from an objective point of view. And serving the public.”

The task is much different from the early years, when someone hung out the side of a helicopter with a shaky shoulder camera and the pilot narrated live. Now, a quarter-million-dollar gyro-stabilized camera, secured under the aircraft, provides mug-shot close-ups from 1,200 feet up. Most pilots no longer talk on TV; because of a deadly 2007 collision in Arizona involving two TV copters, a reporter is now in the second seat to leave the pilot undistracted.

“Not everyone can do it,” said Tim Lynn, who retired from KTLA in 2020 as one of the city’s last pilot-reporters. But after years in the air, “the flying part becomes second-nature, like driving your car.”

The stations are paying at least $1,200 to $1,600 per hour for the copters, according to Larry Welk, whose company leases aircraft and pilots to television stations. Welk has seen the practice evolve. He was the first news copter pilot over the 1994 low-speed pursuit of O.J. Simpson, the former football star who fled rather than face arrest in the slayings of his ex-wife and a male friend.

Television viewers worldwide were spellbound for the hour-long live chase, and thousands more people lined freeways and overpasses to cheer as Simpson passed in a white Bronco.

“It was electric. Everybody was focused on O.J. and this unfolding drama,” Welk recalled recently. “I think it was a turning point in our consumption of live news. It contributed in a major way to the rise of 24-hour news cycle.”

Stacy Scholder was a producer in Los Angeles newsrooms for more than a decade. When these pursuits began, “it was pretty much just ‘launch the copters and switch the programming,’ ” she said. “From a news perspective, we could sort of justify it by saying, well, this is an LA freeway or this is a community and we need to get the word out.”

These days, however, she does little to hide her ambivalence.

“What’s the value here?” wonders Scholder, now a professor of practice at the University of Southern California. “I just think it’s kind of cheap thrills, really.”

But rewarding ones for the stations. News directors keep their teams in the air all day to be the first over a scene during “sweeps” months when stations fight fiercely for viewers to set ad rates.

And for many Angelenos, it’s a guilty pleasure. Apps alert chase aficionados to breaking pursuits, and Twitter lights up with homemade commentary.

“What is so fascinating, ultimately, is that there’s this live-action drama,” Mundel said. “Nobody really knows how it’s going to end. Nobody, right? The cops don’t know. The driver doesn’t know. And the viewer doesn’t know. And so we’re all kind of just along for the ride.”